Improving the management of Scotland’s natural assets at a landscape-level for ecological, economic, and social outcomes is a priority for the Scottish Government and its partners. Adaptive management is one way to achieve this objective and is about connecting the ‘doing’ of natural resource management with ‘learning’ about the context of the management situation, and the responses and effects of the management actions. We provide a series of lessons learned from five studies that cover a range of landscape-level management situations, including upland and lowland areas. These vary from improving agricultural land management in a small east coast catchment (3500 ha) to the management of White-tailed eagles over large areas of the west coast. We have made 14 specific recommendations based on: understand the situation, direct stakeholders, and shared purpose; focus on the social relationships of landscape-level management; and assess ecological, economic, and social outcomes at every step of the adaptive management cycle.

Stage

Directory of Expertise

Purpose

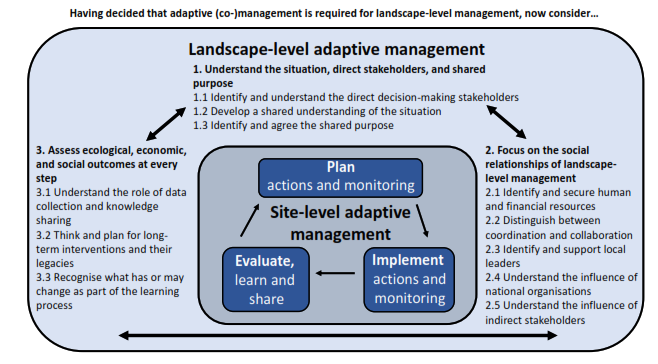

Learning how to manage Scotland’s natural assets at a landscape-level for ecological, economic, and social outcomes is a priority for the Scottish Government and its partners. A landscape-level approach will be needed for Scotland’s green recovery and specifically in the Regional Land Use Partnerships – both prioritised by the Scottish Government in their 2020 Programme for Government. Adaptive management is one way to achieve this objective; where adaptive management is a structured and systematic approach to supporting decision making, planning, action, and evaluation of those actions (Figure 1). Adaptive management can be undertaken within a property (areas managed by a single individual or organisation) and is increasingly used to intervene at a ‘landscape’ level involving multiple properties and social actors. In this research, we have focused on landscape level management of natural assets across multiple properties and involving multiple actors.

This case study provides practical insights to support policy makers and practitioners interested in implementing landscape-level management for ecological, economic, and social outcomes. It summarises lessons learned from five ongoing studies using landscape-level management of natural resources for ecological, economic, and social outcomes. Our findings and recommendations focus on what you may need to consider when implementing or supporting landscape-level adaptive management.

Figure 1. Recommendations to guide landscape-level adaptive management

Results

The five studies cover a range of landscape-level management situations, including upland and lowland areas. These vary from improving agricultural land management in a small east coast catchment (3500 ha) to the management of White-tailed eagles over large areas of the west coast including Argyll & Lochaber and Skye & Lochalsh (See Box 1 at the bottom). Our findings are based on interviews and workshops with researchers involved in these five studies, and feedback from 11 stakeholders representing organisations involved in landscape-level management.

In Table 1 we present 14 recommendations spanning ‘Understanding the situation, direct stakeholders, and shared purpose’; the importance of a Focus on the social relationships of doing landscape level management’; and the need to ‘Assess ecological, economic, and social outcomes at every step.’

Table 1. Recommendations when considering landscape-level management

|

1.Understand the situation, direct stakeholders, and shared purpose Expect to spend significant time and resources understanding the situation, identifying and engaging possible direct stakeholders, and agreeing a shared purpose and desired outcomes before work ‘on the ground’ can start; revisit this recommendation in future adaptive management cycles. |

|

1.1 Identify and understand the direct decision-making stakeholders Try and understand the main decision-making stakeholders (often land managers) and their perspective in terms of their objectives and preferences, before trying to agree a shared purpose and how it may be achieved - as a basis for a trusted and equitable partnership. |

|

1.2 Develop a shared understanding of the situation When starting to plan landscape-level adaptive management, consider what the landscape comprises in terms of diverse ownership and management arrangements, and establish a shared understanding of the current condition of the natural assets and the pressures they face. |

|

1.3 Identify and agree the shared purpose There is not always agreement over the exact nature of the problem to be managed, and it can take time to develop a shared purpose and to identify shared opportunities. If there is no existing shared problem framing and purpose, then more time and resources (including facilitation) may be needed. |

|

2. Focus on the social relationships of landscape-level management Social relationships are at the heart of landscape-level adaptive management and are closely connected to achieving successful ecological outcomes and, therefore, relationships need explicit support and resources. |

|

2.1 Identify and secure human and financial resources Landscape-level adaptive management requires human and financial resources for the interventions and for the processes of coordination or collaboration; these resources may need to be long term if the coordinated or collaborative action is needed for several years to ensure social and ecological outcomes. |

|

2.2 Distinguish between coordination and collaboration It is important not to conflate landscape-level interventions with collaboration (where individuals work as a group); so, recognise when adaptive management occurs through coordination (where individual actions are coordinated by one individual) and when it is collaboration. These processes need different types of support and both need to be resourced. |

|

2.3 Identify and support local leaders Depending on the purpose and situation, careful consideration is needed of who takes leading roles and how leadership can be supported and sustained over time. |

|

2.4 Understand the influence of national organisations There is a need to understand how national organisations’ objectives and remits (even when not directly involved) may influence adaptive management processes. It is important to recognise their influence on decision making (e.g. as a regulator or as a supporter). |

|

2.5 Understand the influence of indirect stakeholders In addition to identifying and working with direct stakeholders (1.1) and national organisations (2.4), it is important to take account of indirect stakeholders, including public opinion, and how these views can influence the appetite for and success of adaptive management. |

|

3. Assess ecological, economic, and social outcomes at every step As learning takes place across every step of the adaptive management cycle, it is important to monitor ecological, economic, and social outcomes, and to analyse and reflect on learning throughout the cycle rather than wait until there are ecological outcomes to assess. |

|

3.1 Understand the role of data collection and knowledge sharing A landscape-level adaptive management process needs to consider how data will be used, and by whom for what purpose. Improving how knowledge is generated, collectively interpreted, and shared is likely to improve the adaptive management processes. |

|

3.2 Think and plan for long-term interventions and their legacies Supporting landscape-level management needs to recognise the long-term nature of the management actions and their legacies, and plan for long-term interventions even when funding is short-term. Thinking long-term requires regular reviews of purpose and process. |

|

3.3 Recognise what has or may change as part of the learning process Ensure that all changes, whether positive or negative, intended or unintended, are captured and learnt from. Any learning also needs to recognise when changes have not or will not occur in the current situation. |

Benefits

Adaptive management is needed for the planning, implementation, and evaluation of interventions (management actions) that are aimed at providing one or more benefits e.g. individual or multiple measures in the Scottish Rural Development Programmes (SRDP). There is a need to understand the effectiveness of these actions in a more systematic way, considering trade-offs and win-wins. The traditional adaptive management cycle typically involves one actor e.g. a farmer on one site, has been adapted for additional aspects when considering implementing adaptive management at the landscape-level with multiple actors (Figure 1), including the need to record decisions and learning at each step.

The recommendations from these studies illustrate that ‘process’ is at the heart of effective and efficient landscape-level management. The adaptive management cycle implicitly covers the lifecycle of a project or partnership, moving from starting through doing to learning from projects and partnerships.

The recommendations are designed to be strategic level prompts for discussion and thinking rather than specific guidance for partnership or project management, given that many useful guides already exist.

We believe the diversity of our studies suggests that these recommendations are relevant for most landscape-level adaptive management cases in Scotland – seeking to adapt and learn in order to improve the quality and extent of their natural assets, to support sustainable land-based industries and vibrant communities.

Box 1. Summaries of the five studies

|

Balruddery Sustainable Catchment Programme This study is exploring the potential for collaboration between farmers within the catchment to improve the effectiveness of agri-environmental management. The Balruddery Catchment is an area of approximately 3500 ha situated to the west of Dundee City on the north of the River Tay. It is an informal group of neighbouring farmers that has the general purpose of gaining and sharing knowledge about each other’s practices and that of the James Hutton Institute Balruddery Research Farm which lies at the geographical centre of the catchment. Cairngorms Connect This study is based on Cairngorms Connect: a voluntary partnership between neighbouring land managers; Glenfeshie Estate (WildLand Ltd), Inshriach (FCS), Invereshie & Inshriach (SNH), Rothiemurchus (FCS), Glenmore (FCS), and Abernethy (RSPB). The case study is part of a wider research project which is exploring what influences bring about changes in management, and what impacts formal and informal collective arrangements have on landscape-level management and its adaptation to change.

East Cairngorms Moorland Partnership This study is based around a group of private, public, and non-governmental organisation owned estates in the Cairngorms National Park including Mar Lodge (National Trust for Scotland), Mar, Invercauld, Balmoral, Glenavon, and Glenlivet (Crown Estates Scotland). This study is part of a research project which explores what influences bring about changes in management, and what impacts formal and informal collective arrangements or groups may have on landscape-level management and its adaptation to change. Lunan – Water for all Project This study is based on a research project that aimed to introduce a new water management scheme to provide multiple benefits in the catchment area. These benefits were to improve water quality to protect biodiversity in wetlands, reduce flood risks, and improve water availability for irrigation. This scheme required collaboration and agreement amongst the multiple stakeholders (riparian owners, farmers and their representatives, conservation agencies looking after the wetlands, rivers trust concerned with fisheries, local council responsible for flood management) around the installation/modification of hydraulic structures and their funding and management. It also required ongoing development of a catchment scale hydraulic model of the impact of management on flows.

White-tailed Eagle Action Plan The study is based around a national partnership that implements adaptive management through the White- tailed Eagle Action Plan (2017 – 2020) in a long-term conflict around the re-introduction of White-tailed eagles and sheep farming. This study is located on the west coast of Scotland, covering parts of the Highlands and Islands region. The current management is focused in the areas of Skye and Lochalsh, and Argyll (and the Isle of Mull), and Lochaber. |

Project Partners

- Cairngorms Connect

- Cairngorms National Park Authority

- NatureScot (formerly Scottish Natural Heritage)