In recent months population trends in remote and Sparsely Populated Areas (SPA) of Scotland have become a political issue, not least due to fears about the likely impact of post-Brexit migration policy. However, this is just a new facet of a longstanding matter of concern which seems to touch a nerve in the national consciousness. Whilst more accessible rural areas have growing populations, the SPA continues to decline, and if recent trends continue, seem to face a bleak future. However, some suspect that the tide is already turning in some parts of the Scottish Islands, in a way which should not only change the assumptions underpinning our projections for the future but should cause us to reflect on the approach and ethos of policy at both local and national levels. This case study discusses the evidence-base upon which such an assertion may be judged, in terms of official statistics, indicators based on administrative data, and more “anecdotal” evidence. This material represents the initial outputs of a new SEFARI Responsive Opportunity Fund project called Islands Revival.

Stage

Directory of Expertise

Purpose

Our previous research on the Sparsely Populated Areas in Scotland suggests a decline of 25% in total population and one-third in the working age population by 2046. The key driver of this trend is the legacy effect of out-migration of working age people in previous decades. The only effective way to reverse this trajectory would be substantial net migration through retention and attraction of economically active people, including return and in-migrants.

Recent anecdotal evidence suggests that, on some islands at least, the demographic tide may be turning, with young people increasingly choosing to stay or return. Evidence for this is mostly informal and piecemeal, and any change in trajectory is unlikely to show up in official National Records of Scotland (NRS) projections for a number of years.

Demography probably has the best track record of any kind of forecasting within the social sciences. This is because a substantial part of future population change is determined by (age specific) birth and death rates, and current age/gender structures. The former change very slowly and vary little between different areas within the same country.

The “wild card” is migration. Patterns of migration can change relatively quickly, in response to a complex range of factors which are very hard to predict. Official population projections, like those produced NRS, usually do not attempt to predict future changes in migration, and, instead, assume that recent trends will continue. This is a very reasonable approach, and the results are helpful, if there is no “sea change” in the rate, or geography, of population movement.

In addition to projections, the NRS provides Annual Population Estimates for Council Areas and Small Area Population Estimates (SAPE), at a data zone level. These, in effect, fill in the trend between the decennial censuses. At this stage in the cycle (2019) they are effectively projections forward from the last census in 2011.

The two key elements of the estimation procedure are:

- Natural change is estimated using a conventional cohort component model. One-year age groups are “aged” by a year, births are added, and deaths subtracted. This is a relatively simple mechanical process, which is hard to question. Adjustments are made for prison populations, armed forces personnel and students.

- In the absence of a population register (such as those established in other European countries) the NRS uses administrative “proxy migration” data.

These calculations are carried out every year, for all 6,976 data zones in Scotland. Every 10 years, when Census data becomes available, the population estimates are harmonized with them.

This is a complex and sophisticated estimation process, with relatively good data sources, which are constantly improving. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind the fact that these data are still estimates, not empirical observations. There are several ways in which the estimates may diverge from reality, especially relating to the migration proxies.

Results

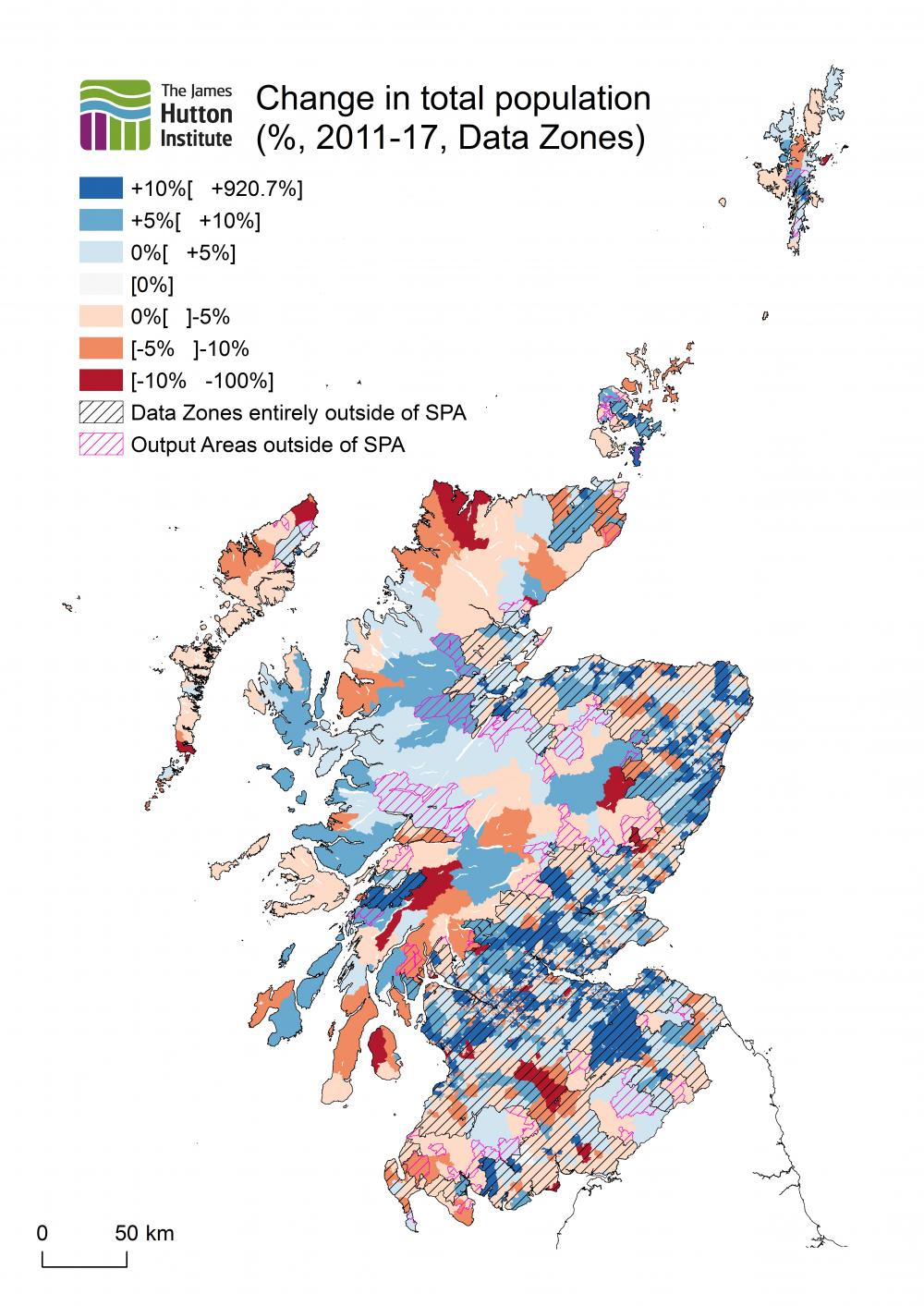

Our Islands Revival project is a SEFARI Gateway Responsive Opportunity Fund project that considers the pattern of population change in the Scottish Islands, since 2011, as revealed by the NRS SAPE data. It then reviews independent proxy indicators, to check if there is any evidence that actual population change differs from the estimated pattern. Overall, the data zones are estimated to have lost 1.8% of their population, while the rest of Scotland exhibited a 2.5% increase in population (Figure 1).

Focusing in on the islands, there are some pockets which have shown growth in population (according to the SAPE). These include Unst, Northmavine and South Mainland (Shetland), West Mainland, S. Ronaldsay (Orkney), Benbecula and Barra, Central and Southern Skye, Eigg and the Small Isles, Colonsay, Jura and Islay.

In the case of some of these, one can associate this growth with a town which is now within commuting distance (Lerwick, Kirkwall, or Stromness). In other cases, there is a local economic activity which perhaps provides an explanation – the Sullom Voe oil terminal, the airport at Benbecula. In other cases tourism may provide an explanation (Skye, Barra). For Eigg, community land ownership may well provide an explanation for population growth.

Figure 1 - the pattern of population change between 2001-2017 in data zones which are fully or partly within the SPA boundary.

Figure 1 - the pattern of population change between 2001-2017 in data zones which are fully or partly within the SPA boundary.

How do these estimates match the reality of recent population change in the islands? This is a tough question to answer, because the data which is used to estimate migration (Community Health Index) is not publicly available. There are a few potentially useful alternative indicators, which are available to the public. These include school roll records, which are published by the Scottish Government, and GP surgery patient lists, which have been published by the Information Services Division (NHS National Services Scotland).

We have mapped both these using published contact details and postcode records. The results are tricky to interpret. For example, an increase in a school roll does not necessarily indicate an expansion of the local population of children, it may instead reflect the complex consequences of the closure of another school nearby. So far, we have not seen anything in these maps that suggests that the SAPE (Figure 1) is “missing” hidden enclaves of population growth in the islands.

Nevertheless, it is important not to neglect another potential source of information which is all too often neglected by policy analysts: Members of the local community are usually quick to detect a change in the way migration is affecting the local population. It is for this reason that the “Islands Revival” project is launching a blog as a means of collecting anecdotal evidence from across the Scottish Islands. For further details, visit the project website and follow @IslandsRevival on Twitter. Later in the summer the project will hold a workshop, in an island location, in order to discuss the evidence which has accumulated through the blog, and to discuss what we have learned about how migration to the islands of younger, economically active families might be encouraged and facilitated.

Benefits

The findings of the Islands Revival project are anticipated to:

(a) Suggest improvements to the evidence base for more realistic assumptions about migration in population projections for the Scottish Islands.

(b) Give clear indications of the potential drivers of population growth which should feature in policies to mitigate population decline.

This will be especially important over the coming months and years with the development of the National Islands Plan, which aims to increase population levels in island communities. In addition, Brexit negotiations provide an opportunity to re-assess the barriers to migration into island areas and to ‘reboot’ Scotland’s rural economy. This will include developing more responsive migration indicators and evidence on Scottish islands to support effective policy-making and development initiatives, and could also include a pilot programme to boost international migration, as envisaged by the UK Migration Advisory Committee in their recent report on the Shortage Occupation List.

Project Partners

- James Hutton Institute

- SRUC

- CoDeL (Community Development Lens)

- Community Land Scotland