On April 14th, 1935, the largest dust storm in American history occurred. A black cloud carrying 300,000 tons of topsoil from the Great Plains deposited dust as far away as New York. This day was the culmination of a perfect storm of events, ravaging millions of hectares of farmland.

After the Civil War, a series of land acts incentivised pioneers to move west and take up farming. These acts generated a massive influx of new farmers to the Great Plains grasslands. Rising wheat prices encouraged farmers to plough up millions of acres of grasslands to capitalise on surging prices for wheat and other crops. As quickly as prices rose, they then fell as the Great Depression hit the US. In desperation, farmers ploughed up even more grassland, attempting to squeeze in an additional harvest in the hope of breaking even. Next came the drought.

In 1931 severe drought swept across the great plains, causing widespread crop failure. Many pioneers had adopted the superstition “the rain follows the plough.” So, they continued to plough, certain that favourable weather and rain would follow. Instead, they compounded the problem. As more grasslands were ploughed, more bare soil was exposed, and the extensive root systems that held the soil in place and supported water infiltration were gone. The small amount of rain that did fall, ran off the soil surface, and quickly evaporated. Without living roots and fungal networks to hold soil in place, strong winds kicked up soil and produced dozens of blackout dust storms each year. The dust storms peaked between 1934 and 1935 when an estimated 1.2 billion tons of soil were lost across 100 million acres. Dust from the storm reached the East Coast and obscured views of the Statue of Liberty. Policymakers started to take notice.

In March 1935, when Hugh Bennett, Director of the Soil Erosion Service, testified before Congress, he could point out the window at the dust as he argued for immediate action. Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal was the start of the much-needed action. As part of the New Deal, Congress established the Soil Erosion Service and the Prairie States Forestry Project.

These projects incentivised farmers to plant trees as windbreaks across the great plains. Over 7 years, the Civilian Corps, born out of this project, was responsible for planting more than 200 million trees across 6 Great Plains states. The Civilian Corps later became what is known today as the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. They estimate that the US today still loses nearly 2 billion tons of cropland soil each year.

Soil erosion remains one of the most pressing agricultural issues worldwide. It is still happening - the intensive way we farm is destroying and degrading the very basis of our entire food system, healthy soil. Soil degradation is defined as a change in soil health status resulting in a diminished capacity of the ecosystem to provide goods and services. Globally around 33% of the world's soils are degraded. Soil degradation is estimated that it will affect 90% of the soils globally by 2050, meaning almost all global ecosystems and populations will be directly affected.

Europe is an important food producer globally, in part because of its abundance of agriculturally productive soils. However, management practices that maximise yields have caused losses in soil organic matter, poor soil structure and reduced water-holding capacity, and have adversely affected the microbial communities that are the drivers of many soil processes. In Europe 39% of the farmland is in a degraded state with nutrient imbalances, whereas measurable soil pollution through pesticides is 48%. Intensive agriculture, urban sprawl and unsustainable forestry activities are the top reported pressures to habitats and species, the EEA report says. This involves the pollution of air, water and soil, and also impacts biodiversity and habitats. Moreover, the flooding damage have become a regular occurrence in Europe. Our degraded soils are not able to take up water anymore when it rains, which leads to flooding damages as well as droughts. This then also leads to crop losses and effects our food security in Europe.

Rill erosion, Scotland (Credit: Lorna Dawson)

Soil exposed to erosion on intensively grazed fields (Credit: Alöna Roitershtein)

The case is clear, we need to shift away from a destructive agriculture to one that builds soil health, and we need to support farmers financially in making that shift.

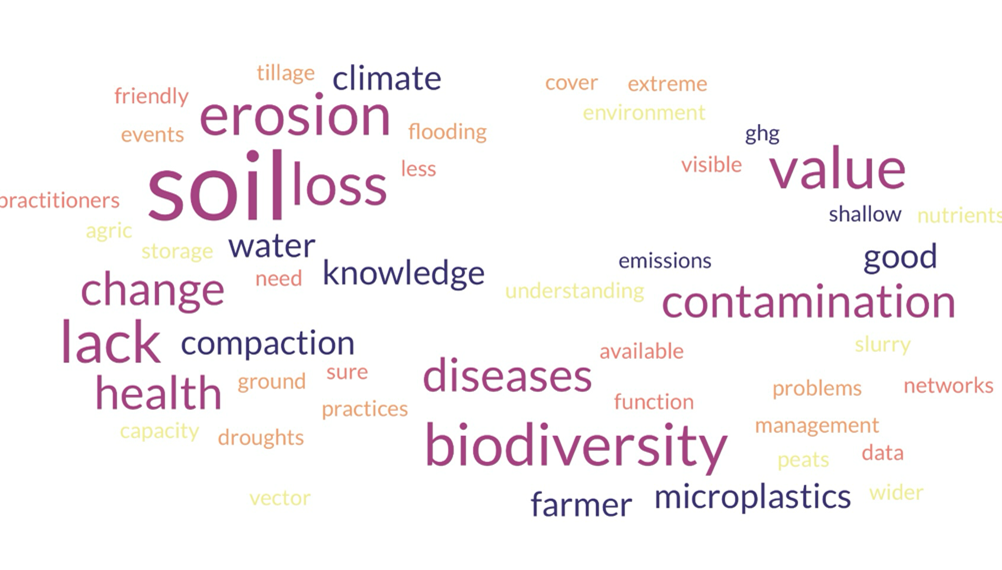

Record-breaking rain recently in the UK left fields of crops under water and livestock's health at risk, adding to pressures on food producers. In Scotland, on the east coast, Storm Babet caused dangerous floods as the east side of Scotland was not accustomed to such a large amount of rain in a brief time period. Flooding and extreme weather linked to climate change will undermine UK food production and security. There has been "substantially reduced output" and "potential hits" to the quality of crops due to many weeks of intense rain as reported by the NFU. Our UK farmers are on the front line of climate change - one of the biggest threats to UK food security. Scottish scientists and policy makers also consider climate change, soil loss through flooding, loss of biodiversity and contamination as some of the main threats to agricultural soils.

The main perceived threats to Scottish agricultural soils, as a word cloud from feedback from scientists and policy makers at a CXC stakeholder working group, Edinburgh, August 2024 (Credit: Lorna Dawson).

Effect of a large amount of sudden rainfall on unprotected soil, causing rill erosion and loss of topsoil (Credit: Lorna Dawson).

The weather extremes could soon become commonplace - so we need to prepare, adapt and recover from our changing climate in the short and long term so that we can continue to produce nutritious food and care for the countryside. That all starts with good soil care.

It is not however the same type of care for each soil type. Scotland has a wide variety of soil types, and there are different risks associated with different threats, for example, soil erosion. This is because our soils are created from a range of different rocks and sediments by several processes controlled by the climate, what has been and is currently growing there, and the position of where the soil sits within the landscape.

Different soils in a multifunctional landscape, Glensaugh (Credit: Lorna Dawson)

Soil health is like a three-legged stool, and its stability depends on the health of these three legs – the physical, chemical and biological health, driven by the growing plants, photosynthesising and exuding carbon below ground from root turnover and exudation, and the animal dung stimulating microbial processes, all building the soil aggregate stability, structure, and life in soil. However, our soils can be damaged by several processes, including erosion, compaction and loss of organic matter. Degraded soils can be a problem, not just for the soil itself, but also for people and the wider environment. Soil erosion can cause pollution in rivers and wider catchment areas. We need to protect our soils so that they can continue to provide the benefits we need, now and in the future. So where does this all leave us? We need to secure the stability and functionality of that three-legged soil stool. Healthy soils.

Healthy soils need all legs to stay healthy. Healthy soils provide a wide range of benefits. Some of these benefits are obvious, such as growing food, while many are less clear, like filtering water, reducing flood risk and influencing climate. Soil makes many important contributions to the goods and services required by society - providing nutritious food, clean water, clean air, timber, culture and play a key role in protecting and enhancing biodiversity and mitigating climate change. Together this ensures our sustainable future. For all soils to be sustainably managed, there is a need to develop an overarching policy for soils to set and implement clear strategic targets, across all types of land use, and all policy areas, against which soil health could be enhanced and maintained.

In practice, this needs the scientific community to work closely with land managers, farmers and crofters, together to identify targets, to be informed by evidence, gained from the UK and Scotland’s excellent capacity in soil science. The scientific community are working alongside farmers and policy makers so that our most up-to-date evidence is integrated into both policy and practice.

Much of such work is already happening. For example, recent scientific advances have spurred interest in how microbial communities can support soil health, food quality, and human health. In addition, Scottish Policy makers are taking notice of soil in the Scottish Government’s Vision for Agriculture. The Agricultural Reform Route Map outlines how it is designed to help businesses understand carbon emissions and sequestration and potentially lower emissions and increase sequestration and efficiencies, through carbon audits, soil sampling and analysis. On the list of audits/measures that make up the Whole Farm Plan, one is Soil Sampling (and all those who have completed a Single Application Form this year were recently sent a letter with these details).

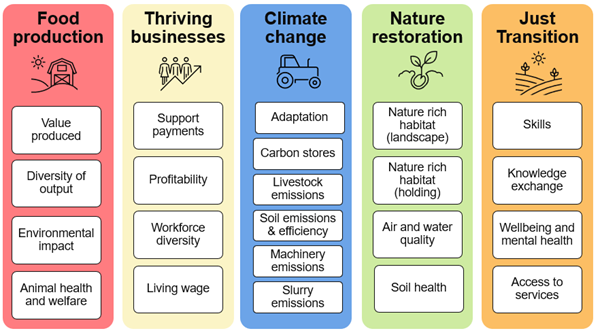

The Draft Agriculture Reform List of Measures has been developed by the Scottish Government officials, which will be the basis for stakeholder engagement and monitoring development (see image below) with key outcomes of Food production, Thriving businesses, Climate change, Nature restoration and Just transition. This work will be supported by a systematic monitoring programme at different scales.

High Level Outcomes within the draft outcomes framework (Source: Kate Dickenson, Principal Research Officer - Agriculture, Food and Drink Analysis, RESAS, Scottish Government)

Within the Scottish Government’s Agricultural Reform Route Map, soil is an integral part - included as building carbon storage, reducing emissions, improving air and water quality, and building Soil Health through managing ALL soils to enhance biodiversity and ecosystem health and thus minimise loss and degradation.

To achieve this, land managers must be part of the process, and in tandem, should be supported through outreach and engagement activities delivered by advisory services that have recognised expertise in soil science, so that sustainable soil management is embraced as a positive activity for the benefit of all. It requires knowing how best to treat and communicate information about our many and diverse soils in Europe, the UK and indeed, in Scotland. We must exchange knowledge effectively and clearly about soil and innovation to farmers, by explaining about the importance of all three legs of that soil stool - the physical makeup to withstand climatic events and not allow loss, the chemical status optimised and efficient for the growing plant, and the lifeblood - the underground biological food web to keep it functioning well now and for future generations.

Work has been commissioned by SEFARI Gateway, supported by the Scottish Government, to carry out an assessment and analysis of the current and emerging issues experienced by EU Member States in the development and implementation of their Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems (AKIS) under the EU CAP Network, to help inform how best to support this knowledge exchange in Scotland. The project considered all participants in agricultural systems: supply chain actors, farmers, crofters, farm advisory services and advisors, land-based business organisations, and research and education providers - including research institutes, universities and colleges, and how knowledge exchange within and between those systems can be supported by policy.

Other projects, undertaken by SEFARI researchers withing the current and previous Scottish Government’s Environment, Natural Resources and Agriculture (ENRA) strategic research programmes, look at the range of Soil Health and Soil Management issues and practices.

Soil sampling at the scale of a footmark (Credit: Lorna Dawson)

If we continue to work soils without care and attention, without regularly replenishing the organic matter, without building up good soil structure, without credence to contours, without including hedges, dykes and trees, without promoting a healthy biodiversity above and below ground, without ground cover, without control of nasty inorganic and organic potential pollutants, then we will fail. The fact that there are more organisms in a teaspoon of soil than people on the planet, illustrates the true extent of the nature of life found in soil and its potential vulnerability.

In a recent report by the Environmental Standards Scotland (ESS, October 2024) it was highlighted that degradation of soil has a real economic impact. In Scotland, erosion, compaction and reduced crop yield caused by lower water retention, cost the economy up to £125 million per year – and the true cost of degradation is likely to be significantly higher. They state that for every 1% increase in flooding associated with soil degradation there will be an increase in local authority flood damage costs of £2.6 million per year in addition to insurance claims of up to £75,000 per property for a single flood event. The ESS state that under its commitment to keep pace with EU law, the Scottish Government should bring forward legislative proposals that reflect the proposed EU Soil Monitoring Law and Nature Restoration Law by introducing a statutory duty to protect and monitor soil, creating mandatory targets for restoration of drained peatland soils and reassessing contaminated land and soil sealing policy. The legislation could build upon previous work undertaken and recent work on monitoring by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the James Hutton Institute.

Prevention is better than cure. Prevent the degradation of what is right beneath our feet. Good farming systems, wherever they are, are returning organic matter to the soil, minimising ploughing, maximising cover. It makes biological sense, it makes chemical sense, it makes physical sense, and it also makes financial sense. Care for our soils to function well, produce nutritious food, to build our food security, and avoiding loss of crops and business stability, also for the provision of clean water to drink, for fresh air to breath in the countryside and in our cities. It is not an option, it is essential, as soil is the very essence of our life on earth.

Let's not wait until dark clouds fill our cities, or we lose our valuable crops and soils, and further homes and roads flood with mud, but let us continue to increasingly farm with nature right at our hearts and nurture our soil that lies beneath our feet. In return, our soils will care for us all. Reward the custodians of our soils - farmers. Reward farmers for looking after our earth's lifeblood, soil.

Written by Lorna Dawson