Introduction

Those involved

Thanks to staff at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE), in particular, our hosts for the day, Alexandra Davey and Jasmine Isa Munro, who made sure that we all were well informed throughout the day. Professor Lee Innes, Communications Director, Moredun, one of the Scottish Environment and Food and Agriculture Research Institutes, and part of SEFARI Gateway, helped organise this visit and ensured that we enjoyed a varied and fruitful experience at the garden.

Background

RBGE is a leading botanic garden and is the curator of Scotland’s national botanical collections. It is a global centre for biodiversity science, horticulture and education. They have four Gardens across Scotland which together hold over 13,000 plant species, with over 1,000 of them threatened with extinction. Botanics’ staff, students and volunteers explore, conserve and explain the world of plants and fungi to all people, pushing the boundaries of scientific knowledge, and training and engaging people of all ages to protect and restore our botanic world. With current projects in over 40 countries, they engage both nationally in Scotland and internationally to deliver the vision of a positive future for plants, people, and the planet.

Sessions

The Gardens

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh is recognised as one of the top botanic gardens in the world. It looks after Scotland’s national plant collections and is a hub for biodiversity research, gardening, and education. Benmore Botanic Garden sits on a stunning mountainside on the Cowal Peninsula. It’s packed with history and surrounded by dramatic scenery. It’s especially famous for its towering conifers and beautiful rhododendrons, with plants from the Himalayas, China, Japan, and the Americas. The “Giants of Benmore”—massive redwoods, Douglas firs, Scots pines, and monkey puzzle trees—make for a truly impressive landscape. Dawyck Botanic Garden, in the Scottish Borders, is tucked into a scenic glen and is one of the world’s top arboreta. Thanks to its continental climate, it’s home to rare and fascinating plants from places like Nepal, China, and Chile. The garden’s trails follow in the footsteps of legendary plant hunters like David Douglas (yes, the Douglas fir guy), and the whole place is steeped in botanical history. Logan Botanic Garden, near Port Logan in Dumfries and Galloway, feels like a part of the tropics. Thanks to the Gulf Stream, it has a mild, almost subtropical climate, which means exotic plants from all over the world can thrive there. All of this definitely gives us some great ideas for future visits and collaborations!

We were welcomed to the garden in Edinburgh by Dr Alex Davey, Deputy Director of Science (Research) at the RBGE. As well as her local experience, Alex has field experience in South America, tropical Africa and South East Asia, where her research interests involve biodiversity, herbarium taxonomy, phylogenetics and threatened species restoration. She is also interested in public engagement and collaborating with artists, poets and social scientists to raise awareness of current global challenges, including plant extinction and habitat loss. She is working to develop collaborative research, conservation and training people in China at the RBGE field station on the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain near Lijiang, Yunnan Province.

Alex talking about some of the international projects. Source: Lorna Dawson

We received a great overview of what the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) is all about, and heard about some of the exciting research they’re working on. Their work focuses on three big themes: Discovery Science, Global Environmental Change, and Conservation & Sustainability. A big part of what they do is building up their plant collections and making them accessible to researchers and the public. One great example of their Discovery Science work is DNA barcoding—a technique that helps identify plant species and it works really well alongside traditional methods. They also talked about meta-barcoding of environmental DNA (eDNA), which sounds like science fiction: they can take an air sample and figure out what species have passed through that area—even something as specific as a parrot flying through a forest! These species lists can then help shape local conservation policies.

This DNA work feeds into some major international projects such as the Darwin Tree of Life, International Barcode of Life, and Biodiversity Genetics Europe—all great examples of global collaboration. They also pointed us to a fantastic free resource: World Flora Online, a huge global effort to catalogue plant life and support conservation.

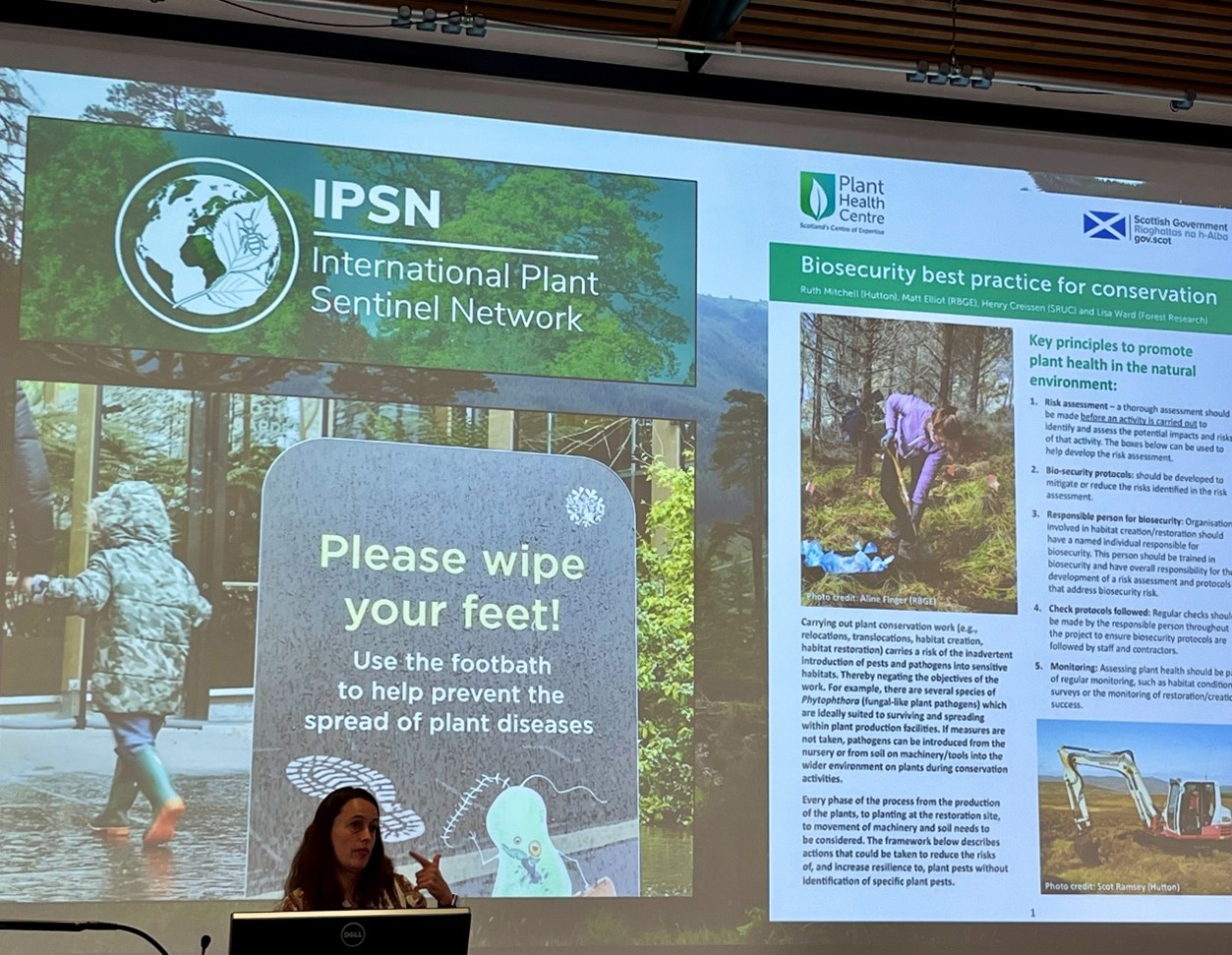

Alex also showed us how RBGE’s work connects globally. For example, under the theme of Global Environmental Change, they’re looking at plant health. In some areas, plants are so vulnerable that visitors have to disinfect their shoes before entering. We also learned about savanna grasslands, where careful grazing and management is essential. Interestingly, these grasslands can store significant amounts of carbon underground! They also touched on the threat of large fires—while small, natural fires are part of the renewal of this ecosystem, the big, destructive fires we’ve seen recently are a real concern.

Under Conservation and Sustainability, we heard about efforts to save rare plants like the Cairngorms’ alpine blue-sow-thistle which is one of the UK’s rarest plants. When conditions allow, it grows in rich mountain grassland and pine and birch woodlands. A few clusters of blue-sow-thistle sit atop remote ledges and gullies on the eastern side of the Cairngorms National Park. Another example was the marsh saxifrage, which needs just the right conditions to thrive—including fresh running water – provided through a ‘Heath Robinson’ custom-built drainage system in the greenhouses. They’re also working on breeding Dutch elm disease survivors to plant out to create more resilient trees.

Alex emphasized that it’s not just about plants—it’s about people too. RBGE is helping communities gain the knowledge and skills to manage land sustainably, like in their work in Nepal. It’s all about collaboration and empowering people to take conservation into their own hands. One standout project is The Good City, where RBGE scientists worked with over 400 young people in Edinburgh to explore nature-based solutions in their neighbourhoods. Using their routes to school as a guide, the children mapped out areas and shared their thoughts—everything from “I like the fir cones for making crafts” to “I hate that woodland because it’s scary.” It was a fun and insightful way to get young voices involved in shaping greener cities. The session wrapped up with a lively Q&A with the Scotia group, covering loads of interesting topics.

The Herbarium

Next up was a really interesting tour of the Herbarium, led by Robyn Drinkwater, who looks after the digitisation and data side of things. The Herbarium is home to an incredible collection—nearly 3 million plant and fungal specimens, some dating all the way back to the late 1600s! These specimens have been gathered over centuries by explorers, scientists, and plant hunters, and each one has its own story to tell.

The Herbarium itself is a massive resource—covering around half to two-thirds of the world’s plant species and spanning over 300 years of biodiversity. The oldest specimen? Collected in 1697! The collection is still growing too, with about 30,000 new specimens added every year. A big digitisation project is underway to make all of this available online, and they’ve already scanned over a million specimens. You can check it out for yourself at RBGE’s Herbarium Search—the images are really high quality. The entire digital catalogue is freely available online at https://data.rbge.org.uk/search/herbarium/.

Robyn showing us the press used to preserve plant specimens in the Herbarium. Source: Lorna Dawson.

When I asked Robyn what her favourite part of the job was, she said it depends on the day—but the thrill of discovering something new is always a highlight. She shared a great example when they recently realised they had a fern specimen from the Alfred Russel Wallace expeditions—something they hadn’t known before! She said she’s always opening drawers hoping to find more hidden gems! Wallace’s notes described colours that are also seen in things like peacock feathers, beetle shells, and even some plant leaves—really fascinating stuff. Other ferns from his collections have turned up in places like Cambridge, Reading, and museums in Paris and Vienna. With 40% of plant species now under threat, collections such as this are more important than ever. They hold clues from the past that can help us protect the future.

Robyn opening up the drawers with interesting specimens. Source: Lorna Dawson

The Library Archives

Our next stop was a tour of the Library, led by Leonie Paterson, the archivist—and she really brought it to life! The Library is Scotland’s national go-to for all things botanical and horticultural, and it’s one of the biggest research libraries in the country. Alongside it is the Archive, which is packed with fascinating old records from RBGE and other related people and organisations. Think letters, maps, drawings, and even quirky objects—all telling the story of how plant science and gardening have developed over the years in Edinburgh.

If you’re curious, you can explore the archive online at this link, and there’s even a special section with lists of past students and gardeners—perfect if you want to see if a relative once trained or worked at RBGE! See https://atom.rbge.org.uk/archive-resources/ for a transcribed lists of students and gardeners in case anyone else wants to check for a relative! One of the highlights of the tour was being given the privilege to vote using the Botanical Society voting box—a fun little piece of history. It used a black ball system where committee members would vote on garden decisions. We got to try it out ourselves—aye or no!

The voting box and record books. Source: Lorna Dawson.

Leonie also shared some brilliant stories from the past. The Garden was founded way back in 1670, and one of its original purposes was to teach trainee doctors about the healing (hallucinogenic and poisonous!) power of plants. Back then, botany was a key part of medicine—even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (yes, the Sherlock Holmes author!) studied plant poisons here. Plants were fundamental to the development of pharmacology and therapeutics. I just want to share a fun bit of history about Arthur Conan Doyle’s connection to the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh during his time as a medical student. Back then, to obtain a medical degree from the University of Edinburgh, students had to study for four years, with a mix of lecture courses each year. Doyle, being resourceful (and needing to support his family), squeezed his classes into half a year so he could work—sometimes as an outpatient clerk for the well-known Dr. Joseph Bell, sometimes as a medical assistant in Birmingham, and even on a whaling ship, the SS Hope, in 1880! Botany was a must-have subject, and students had to attend a three-month course at the Royal Botanic Garden every year—adding up to 50 lectures in total. Exams were hands-on, with lots of object demonstrations, plus written and oral tests.

In 1877, Doyle took a summer course in Vegetable Histology and Practical Biology at the Garden, attending lectures four days a week from May to July. He wasn’t exactly a fan of his medical training. In his memoir Memories and Adventures (1924), he called it “one long weary grind” and had some colourful descriptions of his professors—especially Professor J. Hutton Balfour, who ran the Botanic Garden and taught botany. Doyle described him as a stern, John Knox-like figure who made exams tough, and in return, students gave him a hard time the rest of the year.

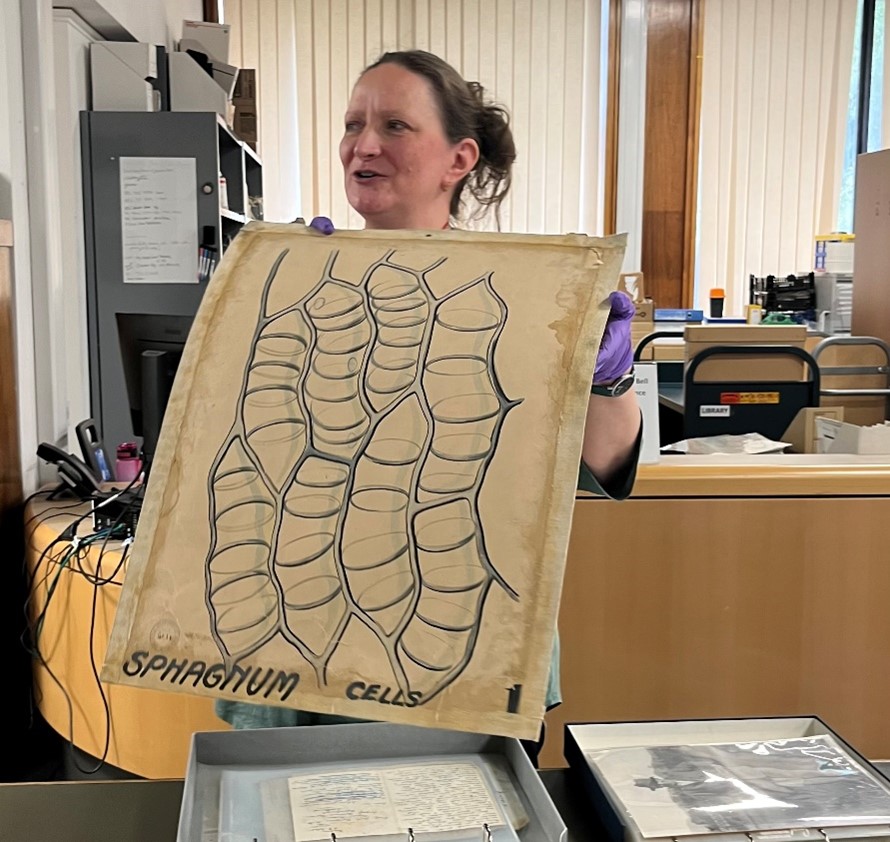

During World War I, moss was used as a wound dressing because of its amazing absorbent and antimicrobial properties—it actually saved lives. Millions of wound dressings made from Sphagnum, or ‘bog moss’, were used during World War I (1914-1918). Dried Sphagnum can absorb up to twenty times its own volume of liquids, such as blood, pus, or antiseptic solution, and promotes antisepsis. Sphagnum was therefore superior to inert cotton wool dressings (pure cellulose), the raw material for which was expensive and increasingly being commandeered for the manufacture of explosives. Charles Walker Cathcart, an Edinburgh surgeon, organised collections of the moss throughout Scotland, and centres for its cleaning and preparation. Most collecting was carried out by women and children (often boy scouts or girl guides) working for long hours in cold, wet bogs. Cathcart’s model soon spread to Ireland and to areas in England, such as Dartmoor, where bog moss was abundant. By 1917-18 collections were being made in Canada, mostly under contract from the British War Office, and in the USA, which had recently entered the war. The preferred species in all countries were S. papillosum and S. palustre. Funny to think about now, but World War I might’ve missed out on one of its most useful medical supplies if it weren’t for two friends in Edinburgh—surgeon Charles Cathcart and Professor Isaac Bayley Balfour, who ran the Royal Botanic Garden. Back in November 1914, they anonymously wrote a piece for The Scotsman newspaper, pointing out that Germany had already figured out how fantastic Sphagnum moss was for wound dressings. They explained that this moss could soak up a crazy amount of liquid and later tests showed the best moss could absorb 20 to 22 times its own weight before it even started dripping. And it wasn’t just water—it could soak up blood, pus, lymph, you name it. It was at least twice as absorbent as cotton wool. Also, cotton wool was becoming hard to source since it had to be imported and was being snapped up to make explosives. Moss, on the other hand, was not only super absorbent—it also had natural antiseptic properties, which made it a game-changer for surgeons and nurses treating wounds on the front lines.

Leonie showing us one of the original drawings from over 100 years ago of sphagnum moss cells. Source: Lorna Dawson.

We also heard about George Forrest, a former herbarium clerk at RBGE who became a legendary plant hunter in China. In 1904, he set off on a dangerous expedition to Yunnan province. A year later, word came back that he’d sadly been killed—but then, a few days later, a telegram arrived saying he was alive and well! He’d narrowly escaped and went right back to plant hunting. One of the most exciting finds in the archive, according to Leonie, is a letter Forrest wrote after that ordeal. She said reading these original letters really brings history to life—and shows that even the most respected figures had their moments of mischief!

With 40% of plant species now under threat, these archives are more than just old papers—they’re full of lessons that can help us protect the planet today as well as providing insights into people’s lives.

Majestic specimens of ancient conifers in the garden. Source: Lorna Dawson

After a refreshing lunch at one of the brilliant cafes and restaurants at the RBGE www.rbge.org.uk/visit/royal-botanic-garden-edinburgh/food-and-drink the group then walked through the gardens and explored some fascinating displays both natural and curated including ‘Girl’ by Reg Butler, 1957.

The Girl, 1956, at the pond. Source: Lorna Dawson.

Summary

We had an absolutely brilliant day at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh! We came away buzzing with new knowledge and great conversations—everything from public engagement and scientific discoveries to conservation, plant collections, DNA, and the importance of biodiversity both here and around the world.

We also got to dive into some unexpected highlights—such as how to preserve plant specimens, turn them into ceramics, treat wounds with moss, and even how to poison your enemies (purely historical, of course!). Oh, and we got to try out the old-school black ball voting system—aye or no?

It was a fantastic mix of people and plants, science and stories. A great day all round!

Lorna Dawson, Knowledge Exchange Broker, SEFARI Gateway

The Gardens of Knowing

Lorna Dawson

In Edinburgh’s heart, where green wisdom grows,

A garden stands tall as the world gently flows.

With petals and data, with roots and with rhyme,

It nurtures the future, one species at a time.

Benmore’s giants rise through mist and through pine,

Redwoods and firs in a mountainous line.

From Himalayas to Americas wide,

Their stories are whispered on each wooded stride.

Dawyck lies nestled in Borders’ embrace,

Where Douglas once wandered with curious grace.

Nepalese treasures and Chilean bloom,

In arboreal silence, they quietly loom.

Logan, where tropics kiss Scotland’s cool shore,

Gulf Stream’s warm breath lets the exotics soar.

Palms and perfumes in coastal retreat,

A subtropical haven where climates meet.

In labs and in fields, the science takes flight,

Barcoding life with molecular light.

Meta-barcoding—air’s silent tale—

Reveals the wingbeat of parrots that sail.

From Cairngorms sow thistles to crab apples rare,

Each fragile life gets meticulous care.

Dutch elms reborn with resilience bred,

Hope in the greenhouses quietly spread.

But it’s not just the plants—it’s the people who grow,

In Nepalese valleys and cities below.

Young voices mapping their schoolyard dreams,

Fir cones for crafts, and woodland extremes.

Alex, a guide through the world’s leafy maze,

With stories from tropics and mountain haze.

She bridges the science with art and with soul,

Restoring the wild, making broken things whole.

So here in these gardens, both near and afar,

We learn what we were—and what we still are.

A million visitors, a million hearts,

All playing their part in nature’s great arts.