Rural depopulation is a topic which seems to have slipped down the policy agenda in Scotland in recent years. The popular narrative about the Highlands and Islands has become more positive – highlighting the growth of Inverness and its immediate hinterland, opportunities for renewable energy, or tourism and leisure based on the region’s rich natural environment.

However our recent Scottish Government-funded research suggests that the issue has not gone away, but has been “hidden” by the way in which boundaries are drawn.

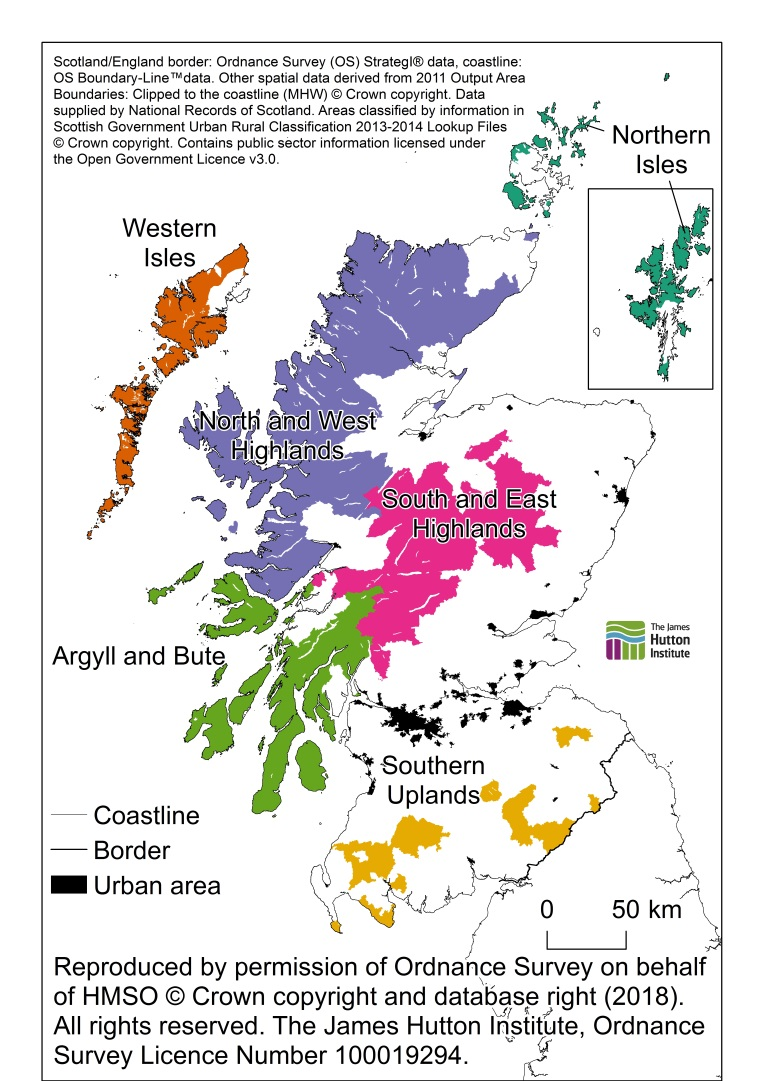

We have defined the most remote and sparsely populated area (SPA) of Scotland. The SPA comprises much of the Highlands and Islands together with parts of the Southern Uplands - this occupies almost half Scotland’s land area, but is home to less than 3% of its population.

Within this area many decades of selective outmigration have resulted in a population structure which is unable to sustain itself without massive in-migration.

The hidden story…

In broad-brush terms the total population of the SPA was in decline during the 1990s. After a brief period of expansion during the first decade of this century, the negative trend is projected to continue through to the 2040s. This will result in a loss of about one-third of the current population.

The scale of this phenomenon is illustrated by the estimated net migration which would be required to stabilise the SPA population – currently about 500 persons per year, rising to 1,300 in the early 2020s.

The shrinking process is likely to be combined with a steady increase in dependency rates (the ratio of children and over 65s to the working age population), primarily as a consequence of the shrinking working age population.

This rather negative prognosis for the SPA contrasts with the more positive future which is foreseen for the rest of Scotland, both rural/small town and urban.

Let’s not jump to conclusions…

In-migration does not equal immigration. The SPA is not, and is never likely to become, a favoured destination for international migrants. The SPA is more likely to be beneficiary of population redistribution processes within Scotland and the UK.

There is no reason to assume that maintaining the population of the SPA at current levels is necessarily the best scenario for the SPA.

Consideration of future demographic trends needs to balance (among other things) potential environmental gains and losses, and the implications for the cost of service delivery to widely dispersed residents.

In addition we need to understand the very complex ways in which twenty-first century mobility and communications technology will impact upon economic activity in or near the SPA.

Are city-based growth policies enough?

The SPA is not a functional geography – in no sense is its economy a closed system. Rather it should be viewed as an area on the fringes of the hinterlands of Scotland’s cities.

It is therefore unlikely to derive many direct benefits from growth policies (such as City Region Deals) which rely upon cities as the engines for regional development.

There is a danger that over-reliance upon such approaches could exacerbate the demographic shrinkage of the SPA. Arguably, in a post-BREXIT world, the SPA could benefit from a tailored “place based” intervention which addresses the needs all sectors of its economy.

What are the implications of this?

Recent calls for “repopulation” of the Highlands and Islands, or a reversal of the clearances present a stark contrast to calls for “rewilding” of extensive agricultural land. Our findings begin to place this debate in an objective, evidence-based, context.

At this stage it would not be prudent to draw any firm conclusions about the need to intervene to support increased levels of migration into the SPA.

Among the issues that we will need to explore during the remaining years of our project are:

- The likely changes in land use associated with population shrinkage (or resettlement), and the associated effects upon the SPA’s environment and ecology as a resource to support the wellbeing of the population of the rest of Scotland.

- The likely medium-term changes in land-based activities within the SPA, as a consequence of changing technology, market developments, and the policy context (not least potential BREXIT effects on sheep farming).

- The implications of increased personal mobility, together with the opportunities afforded by information and telecommunications technology, for the lifestyles and economic activity of residents in, and near, the SPA. Settlement patterns are evolving; population redistribution trends already favour small towns and accessible rural areas at the expense of sparsely populated areas. This is, of course, a very different context for making a living to that of the communities affected by the clearances of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

- The social and cultural implications of in-migration (on the scale which the projection model suggests is required to stabilise the SPA population) and the potential for triggering a “white settler” debate.

- The implications of shrinkage or resettlement for the provision of services – at a time when both public and private providers are struggling to maintain standards.

Andrew Copus, The James Hutton Institute