In Scotland, about 11% of households experienced low food security (reporting reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet) or very low food security (reporting multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake) in 2022-23. Thus, levels of food bank use are likely to be significant in Scotland. However, no official estimates exist of the scale and scope of food banking activities. This report summarises the distribution and activities of food support outlets in Scotland in 2023.

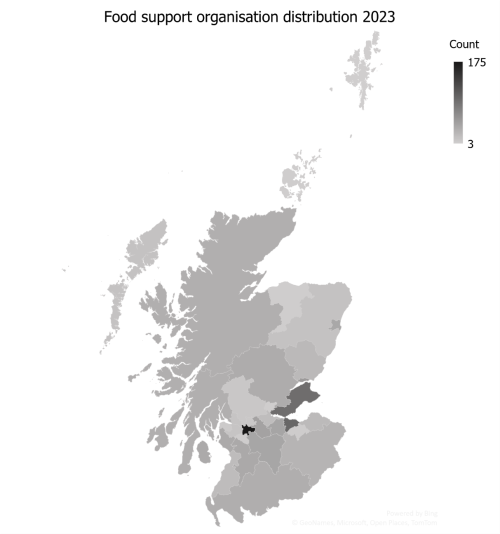

Our research found that the distribution of food support outlets aligns broadly with areas of highest deprivation, with lower concentrations in rural areas and higher concentrations in remote small towns than would be expected if they were distributed evenly across Scotland. These outlets often provide more than food support alone and there are indications that they are coming under increasing pressure.

Stage

Work CompletedDirectory of Expertise

Purpose

Many people in Scotland rely on charitable food provision: official statistics estimate that four percent of households used a food bank in the 2021-22 financial year. In 2023 the Scottish Government introduced its Cash-First plan, outlining nine collaborative policies to help deliver its long-term aim to end the need for food banks.

There are no official estimates of the scale and scope of food bank provision, although data on both were collected by Urban Roots for the Scottish Government in 2019-20.

This report summarises research done in 2023 into the distribution and activities of organisations providing food support (including food banks) in Scotland.

By casting new light on the ‘supply’ side of charitable provision this research provides material for policy discussion and development.

Results

In this section we present data on the number, distribution and activities of food support outlets in Scotland. Using online searches and an e-mail survey, we identified 638 food support organisations, operating through 1,008 outlets. However, this may under-report the total numbers, as some may not have an online presence. Previous research identified 744 organisations providing free or subsidised food through 1,026 venues.

Given the economic challenges of recent years, it seems surprising that there do not appear to be more food support outlets operating in Scotland in 2023 than there were in 2020. Especially as, although official estimates of food insecurity for 2022-23 are not yet available, it has been reported that demand for food support has increased (IFAN 2023; IPSOS and The Trussell Trust 2023). Therefore, it may well be that, on average, each food support outlet helped a larger number of people in 2023 than in 2020.

Distribution of food support outlets

It seems reasonable to assume that food support outlets are located where they are needed. However, because food support organisations are not part of government welfare provision, there is no guarantee that all areas where there is food insecurity will be served by them. There may be areas with relatively high levels of food insecurity, itself indicative of inadequate welfare provision, that suffer the additional disadvantage of a lack of food support outlets.

Thus, we wanted to compare the distribution of food support outlets, as recorded in our research, with the distribution of food insecurity. As there are no official statistics showing the distribution of food insecurity, we used the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). The SIMD shows the relative level of deprivation across Scotland’s 6,976 data zones. All data zones have similar sized populations, so those in rural Scotland cover larger areas than those in towns and cities.

We examined the distribution of food support outlets across Scotland’s data zones in order to identify the extent to which they are concentrated in areas with the highest levels of deprivation (Table 1). Column two shows that, as the level of overall deprivation increases, so too does the number of food support outlets. The Chi squared test produces a less than 0.1 percent probability of this being a chance finding. Thus, food support outlets are concentrated in more deprived data zones.

|

SIMD quintile 1=most deprived 5=least deprived |

Number of food support outlets in overall SIMD quintile |

|

1 |

364 |

|

2 |

275 |

|

3 |

178 |

|

4 |

117 |

|

5 |

62 |

|

Totals |

996 |

|

295.86 |

Table 1. Number of food support outlets by overall and access domain SIMD quintiles.

Note: Food support outlets were allocated to data zones on the basis of their postcode, using the Scottish Postcode Directory. Data zones’ SIMD rankings are from version 2 of the 2020 SIMD lookup file.

The SIMD tends to under-report deprivation in rural areas. For example, access deprivation can be high in rural areas because distances to employment and services tend to be larger than in urban areas and public transport sparser. Table 2 investigates this by examining the distribution of food support outlets in areas coded using the Scottish Government’s six-fold urban-rural classification (UR-6). The location quotients (LQ) in column five show the concentration of food support outlets (column 4) compared with the total population of each type of area (column 3). The number of food support outlets is broadly proportionate to the population in remote rural areas (LQ = 1.09; a fully proportionate LQ would be 1.0), urban areas and accessible small towns. This suggests that Scotland’s remote rural areas may be better served by food support outlets than shown in column three of Table 1; though travel distances are likely to be larger than for urban residents. Accessible rural areas appear to be under-served by food support outlets (LQ = 0.54). However, remote small towns (LQ = 1.73) contain the largest concentration (relative to their overall population) of food support outlets; which probably reflects their long-standing role as service centres for surrounding rural areas.

|

Urban/rural 6-fold code |

Urban/rural 6-fold code name |

Population1 |

Food Support Outlets2 |

Location quotient |

|

1 |

Large Urban Areas |

2,061,049 |

426 |

1.13 |

|

2 |

Other Urban Areas |

1,843,792 |

319 |

0.94 |

|

3 |

Accessible Small Towns |

470,529 |

89 |

1.03 |

|

4 |

Remote Small Towns |

144,514 |

46 |

1.73 |

|

5 |

Accessible Rural Areas |

660,901 |

66 |

0.54 |

|

6 |

Remote Rural Areas |

299,115 |

60 |

1.09 |

|

Totals |

5,479,900 |

1,006 |

Table 2. Distribution of food support outlets across the Scottish Government’s six-fold urban-rural classification (UR-6).

Notes: 1. Population estimates are for mid-year 2021.

2. Food support outlets were allocated to data zones based on their postcode, using the Scottish Postcode Directory. Data zone populations and UR-6 codes are from version 2 of the 2020 SIMD lookup file.

Activities of food support outlets

An important distinction emerging from survey responses, when compared to online sources, is the range of activities undertaken by food support organisations. Three-quarters of food support outlets identified online listed only one activity, whereas more than half of survey respondents claimed to undertake two or more. This makes it likely that most food support organisations undertake a range of activities that might not be obvious to those without direct knowledge of them.

This is relevant to policy, as without gathering data directly from food support organisations the extent to which they provide services, other than free food and drink, may not be clear. Cash-First emphasises the role of Citizens Advice Scotland (CAS) in its case studies, as providers of money advice and as conduits for the provision of emergency financial assistance. However, food support outlets are often also sources of such help and advice. Among survey respondents, the range of support offered included: grants or vouchers for the purchase of food and/or utilities; signposting to other support agencies; and benefits and/or welfare advice.

Therefore, if emphasis is placed on CAS providing emergency funding and advice to people in need, attention is likely to be required in at least two areas. First, awareness of the types of support available from CAS, and the ease with which they can be accessed, needs to be raised. For instance, when surveyed, 35 percent of people referred to food banks in the Trussell Trust network noted that they had ‘received no advice from other services before their latest referral’ (IPSOS and The Trussell Trust 2023, p. 64). Secondly, there is likely to be a requirement, as the first point is addressed, for greater partnership working between CAS and food support outlets in order to facilitate development of the enlarged role envisaged for CAS.

Our research also suggests that food support organisations are starting to move away from the term ‘food bank’. Table 3 shows that 750 food support outlets stated that they provide food and drink products (excluding meals (e.g. in a café or carry-outs) and food retail). Although rarely stated explicitly, it is likely that the food and drink supplied through the means listed in Table 3 is provided free of charge or through payment of a modest subscription.

|

Type of food provision |

Number |

% |

|

Food bank |

398 |

53.1 |

|

Free or emergency food |

89 |

11.9 |

|

Food parcels, packs or bags |

81 |

10.8 |

|

Larder, cabinet, cupboard, shelf etc. |

81 |

10.8 |

|

Food pantry |

59 |

7.9 |

|

Chilled or frozen food |

24 |

3.2 |

|

Other |

18 |

2.4 |

|

Total |

750 |

|

Although 53 percent of outlets operate food banks, a large minority use other terms to describe the food support they provide. In some cases, such as food pantries, this may reflect a different model of provision: pantries typically being subscription-based, instead of the walk-in or referral-based access to free food associated with food banks. However, in a fifth of cases the provision of ‘free or emergency food’ and of ‘food parcels, packs or bags’ would appear to be akin to a food bank, but under a different name. Something similar may also be the case with ‘larders, cupboards, shelves etc.’ and the provision of ‘chilled or frozen food’, although both imply that the range and quantity of food available might be restricted. Such figures, taken together with comments from survey participants, suggest that many food support organisations are choosing not to use the term ‘food bank’ to describe what they do, even when their activities include the provision of free food and drink.

More than two-thirds of survey participants reported receiving supplies from three or fewer organisations. Fifty percent obtain food through a small number of intermediary organisations (e.g. FareShare) and 39.7 percent receive food from multiple retailers. These compare with 39 percent that receive public donations.

Benefits

This case study provides important new evidence on the distribution and activities of food support outlets in Scotland. In doing so, it contributes to the evidence base for food security policy development and evaluation.

Overall, the distribution and activities of food support outlets appears to align broadly with areas of highest deprivation. They are present in remote rural areas and more concentrated in remote small towns than would be expected if they were distributed evenly. However, all this could change easily, as their distribution is not, and is not required to be, uniform across Scotland’s most deprived areas.

Understanding what types and quantities of food and drink products pass through food support outlets is challenging. Survey participants reported a narrow supplier base and that deliveries vary considerably. This is concerning, given that the number of food support outlets appears to have remained roughly the same since 2020 while demands on them have reportedly increased. If heightened demand is coupled with reduced supply then, other things being equal, food insecurity is likely to rise and the resilience of food support organisations to decline. A further benefit of this research is, therefore, that it highlights important ‘supply side’ challenges to building food security for all in Scotland.

Cash-First should help here, as it aims to reduce reliance on free food and drink by ensuring that people get money to which they are entitled, enabling them to use retailers. However, as we report elsewhere, food support outlets provide many of the ‘wrap-around’ services required in addition to cash if the aim of ensuring that all of Scotland’s people become and remain food secure is to be met.

Project Partners

This research was funded by the Scottish Government’s Environment, natural resources and agriculture - strategic research 2022-2027 programme, and is part of the project Building food and nutrition security in Scotland. The project is overseen by a Steering Group containing policy specialists and organisations involved in providing food support.