The continued grazing of the uplands is contentious as the goals of rewilding and farming/crofting often appear in conflict. Any changes to land use will result in cascading impacts through ecosystems, and decisions about land-use need to be informed by data to show that benefits will exceed the disbenefits. Our unique, long-term, large-scale grazing experiment at Glen Finglas provides some key pieces of the evidence on the ecological trade-offs that occur when management is changed. Removing grazing, as rewilding would do, benefits the diversity of important groups like birds, moths and spiders. However, the diversity of groups such as plants and beetles, as well as the population of a key upland bird species - the meadow pipit - benefit from the disturbance brought about by heavy grazing. Only through assessing both the “winners” and “losers” from land use change can we develop appropriate regional or national strategies for land management that will tackle both the biodiversity and climate crises.

Stage

Directory of Expertise

Purpose

At the start of the 21st century there was concern that the uplands were overgrazed. Reforms to agricultural support payments from payment per animal (headage) to area payments were meant to counter this, but there was concern that changed grazing regimes would have unforeseen impacts on biodiversity.

In 2002 the Glen Finglas experiment - funded by the Scottish Government - was established to tackle how changes in grazing would cascade through upland ecosystems. This experiment is unusual in that it is long-term, large-scale and has investigated many different groups of species. The experiment involves 24 grazing enclosures, each measuring 3.3 ha. We established four grazing treatments, replicated six times.

The grazing treatments were:

- Nine sheep per enclosure (High)

- Three sheep per enclosure (Continuing the previous levels of grazing)

- Mixed cattle and sheep grazing with the same stocking as the Continued treatment,

- Ungrazed

A view of upland vegetation at Glen Finglas.

The plots are big enough to contain substantial numbers of meadow pipit territories enabling changes in grazing to be followed through to impacts on the population of the most common upland bird in the glen.

Since 2002 there has been regular assessments of vegetation composition and diversity, invertebrate populations, nesting birds and vole densities. There have been specific investigations into other groups including fox activity, moths and spiders, as well as modelling of carbon stocks.

Results

The meadow pipits were very quick to react to the changed grazing in the experiment. They benefit from increased grazing and from the introduction of cattle which reduce the height of the vegetation and break up the tussocks. This makes the pipits’ invertebrate food more accessible. However, excluding grazers hampers their foraging and they nest at low densities in ungrazed vegetation. In contrast, bird diversity increases without grazing, primarily because of scrub development in the ungrazed plot nearest a wooded ravine (a good seed source).

The left-hand picture shows a fenceline between a typical ungrazed (None) and heavily grazed (High) plot; the vegetation is similar, but taller when ungrazed. The right-hand picture shows the scrub development on the one ungrazed plot near a good seed source.

The left-hand picture shows a fenceline between a typical ungrazed (None) and heavily grazed (High) plot; the vegetation is similar, but taller when ungrazed. The right-hand picture shows the scrub development on the one ungrazed plot near a good seed source.

The vegetation has been very slow to change. This is partly a consequence of the diversity of different vegetation types across the plots as it allows the grazers to focus on their preferred diet. Even increased grazing means that less preferred vegetation is still largely ignored and so responses are limited to small increases in more preferred species. Removing grazing also has limited effects as there are few species capable of responding which remain in the more preferred vegetation and little overall change in grazing pressure on the less preferred vegetation. Tree regeneration has been slow apart from one ungrazed plot near a good seed source.

Herbivorous insects, like moths and plant bugs, benefit from grazing removal, as do many spider species which require taller vegetation. However, predatory beetles are much more abundant in the heavily grazed plots. The taller vegetation favours voles and, consequently, fox activity is higher in the ungrazed plots.

Reduced grazing leads to more carbon storage in the above-ground vegetation. No measurements of soil carbon have been carried out so far but results from other studies suggest that overall ecosystem carbon on the organic soils of Glen Finglas would be relatively unchanged by tree invasion as carbon stored in the wood of trees is roughly balanced by the loss of carbon from organic soils.

Benefits

The research has shown many new insights into the ecology of the uplands and the cascading impacts of management change on a range of groups. However, the long-term, large-scale and multi-taxa approach to monitoring has meant that we can examine the trade-offs involved in decision making about how upland systems are used.

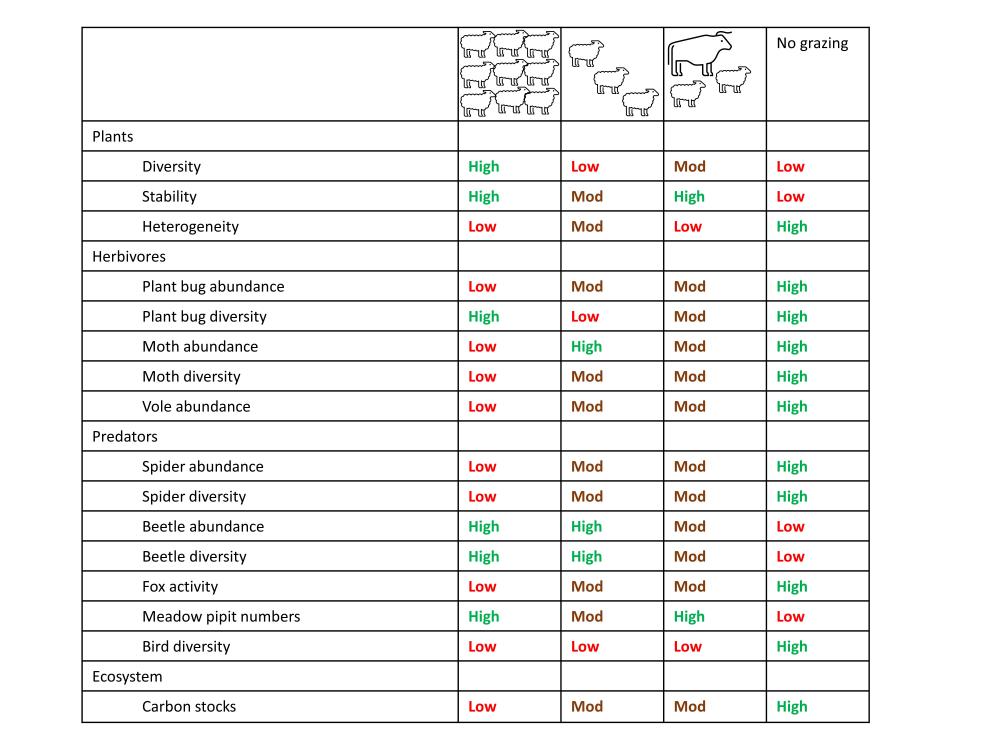

A summary of how the different grazing treatments benefit of different aspects of biodiversity and carbon storage. The treatments are High - nine sheep per plot (2.7 sheep ha-1), Continued - three sheep per plot (0.9 sheep ha-1), Mixed – two sheep per plot and cattle grazing for a month (equivalent to 0.9 sheep ha-1) and None – livestock excluded.

A summary of how the different grazing treatments benefit of different aspects of biodiversity and carbon storage. The treatments are High - nine sheep per plot (2.7 sheep ha-1), Continued - three sheep per plot (0.9 sheep ha-1), Mixed – two sheep per plot and cattle grazing for a month (equivalent to 0.9 sheep ha-1) and None – livestock excluded.

Clearly there is no scenario that benefits every species we’ve monitored. Interestingly the high stocking levels that bring a diversity of plants and beetles is in complete opposition to the high diversity of birds, spiders and other invertebrates associated with grazing removal.

There is much debate about rewilding and the benefits it might bring. What our research shows is that the net benefits of changing management are not straightforward to assess and that any change will result in both “winners” and “losers”. An expansion of scrub and woodland at Glen Finglas will bring a much more diverse bird community, but in turn this would reduce the numbers of meadow pipits and impact the species that depend on them like merlin.

The rewilding debate has often been centred on benefits to biodiversity and carbon storage. However, more nuanced debate on what precise benefits arise from changing upland management are required to ensure that decisions minimise negative impacts on both biodiversity and organic soils.

Project Partners

University of Newcastle