History and Heritage

Orkney’s story stretches back over 5,000 years to the Neolithic period, when people built remarkable monuments like Skara Brae, the Ring of Brodgar, and the Stones of Stenness, which I managed to explore whilst on the island.

Visiting the Stones of Stenness. Source: Lorna Dawson

I also visited Cuween Hill, one of the finest Neolithic chambered tombs, where both people and dogs were interred over 5,000 years ago, a reminder of how deeply humans have long connected with their animals.

Looking out from the chambered tomb of Cuween Hill to the rolling landscape towards the sun. Source: Lorna Dawson

Moving through history, the Norse settlers also left an enduring mark. At the heart of Kirkwall stands the magnificent St Magnus Cathedral, built in 1137 and dedicated to Earl Magnus Erlendsson, Earl of Orkney, sometimes known as Magnus the Martyr and later as Saint Magnus, who was martyred on the island of Egilsay.

Inside Saint Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall. Source: Lorna Dawson

The islands were officially integrated into Scotland in 1472 and later became a strategic hub during both World Wars. Italian prisoners of war famously built the beautiful Italian Chapel, a lasting symbol of resilience and hope.

Inside the Italian Chapel, Lambholm, showing the wonderful art built by Italian WWII prisoners. Source: Lorna Dawson

Nearby, the remnants of Rerwick Head gun batteries stand as stark reminders of Orkney’s wartime role. Today, they overlook a coastline teeming with birdlife. The islands are now a leader in the production of renewable energy, with wind and marine resources generating more electricity than the islands can consume.

Some of the remnants of the Rerwick gun batteries looking out to sea. Source: Lorna Dawson

Science in the Field

Farming has shaped Orkney’s landscape for thousands of years. The islands are famed for their livestock, particularly beef and lamb, and their fertile and diverse soils, shaped by Old Red Sandstone, glacial till, and dune sands.

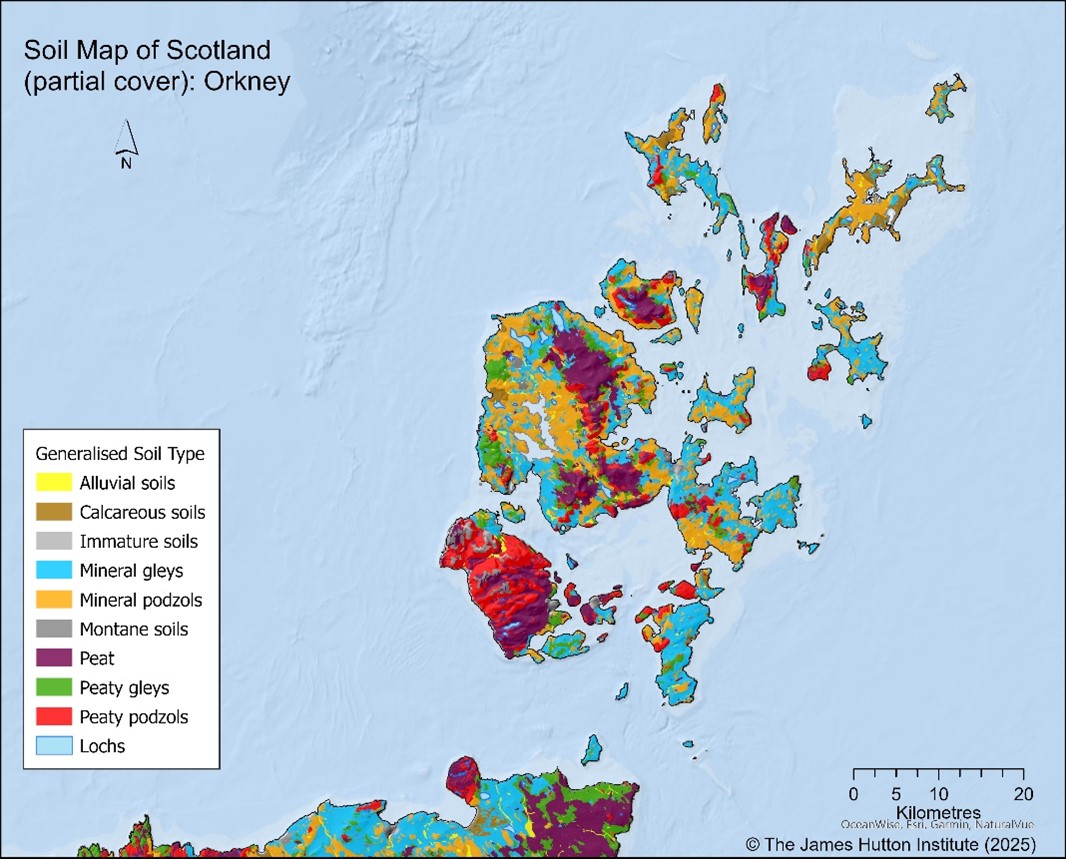

A soil map of Orkney. Source: David Donnelly

Long-term human activity, from seaweed fertilisation to turf cutting, has enhanced soil fertility, while modern research continues to build on this legacy. The James Hutton Institute and UHI Agronomy Institute have collaborated on projects improving Orkney’s bere barley, a heritage crop thriving in manganese-deficient soils where modern varieties fail. This could have major implications for growing under marginal conditions.

In the original field trials at a site on Orkney near Burray which is used to grow commercial bere for Bruichladdich, the researchers first noticed the unique ability of some bere lines to grow well on these poor and naturally manganese deficient soils. In a more formal study funded by RESAS they trialled a range of bere lines sourced from Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles, along with elite modern recommended list lines on Burray soil. The results were staggering in that only the bere thrived in these conditions, producing harvestable grain, while the modern elite lines failed in all cases to flower successfully, with little or no grain produced. In order to determine the genetic control of this trait, Joanne Russell and her team crossed the bere manganese efficient line with a modern elite line and generated a population of 400 lines by traditional introgression breeding and a three replicate trial was sown at Burray this year. The lines were scored for a proxy for manganese efficiency as well as earliness and number of ears harvested to examine grain quality. All lines have been genotyped with 44,000 gene related genetic markers and they are now moving towards identifying the genes or regions of the genome that control manganese efficiency trait in barley. As well as identifying candidate genes, they have also identified lines that will be important for the future sustainable and resilient production of barley, allowing modern varieties to grow in areas as yet unused, but also improving the yield and growth of the traditional bere.

A field of bere barley being sampled by Joanne Russell in Orkney. Source: Joanne Russell

This work combines traditional knowledge with modern genetics to identify traits for sustainable barley production, a perfect example of science aligning with Orkney’s traditional agricultural heritage.

Furthermore, between 2012 and 2015 Karen Scott from the Rowett and Hutton took part in barley and oat growth trials run at Orkney College (UHI). Six different varieties of each (including bere barley) were grown and the nutritional profiles were analysed. The macro- and micronutrient data was compared for three of these varieties with those grown elsewhere in the UK (Dundee, Berwick and north Wales and with data from a Nordic study, comparing growth of samples in and near the Arctic circle (Orkney was the furthest south latitude). Then in 2018 staff at the Rowett partnered up with the Barony mill in Birsay, Orkney to dehull high B-glucan barley grown by JHI that we then used to provide porridge for the volunteers in a human intervention study. Wendy Russell is now currently working with Lynn Collison (Orkney Tea) to explore the impact of growing conditions on the nutritional value and economic opportunities for tea grown in Orkney.

Local Innovation in Livestock Farming

Livestock farming remains central to Orkney’s economy, producing premium Orkney beef and distinctive North Ronaldsay sheep, which graze on seaweed. Dairy farming, however, has declined, with only 12 active farms remaining. The closure of the Kirkwall abattoir has posed challenges, but local farmers are responding with ingenuity.

One inspiring example is Jane Cooper’s “Tiny Trailer Abattoir”, the first of its kind in the UK. Designed to travel between farms, it will reduce animal transport, improve welfare, and restore local provenance to Orkney meat.

Jane Cooper’s Boreray rams George, Corin and Benedict. Source: Rob Flett, BBC

During my visit, I met David Taylor, a livestock farmer from St Margaret’s Hope, who proudly tends a healthy herd of Charolais and Simmental cattle. His passion for quality and care for his animals mirrors the strong farming traditions that define Orkney.

Orcadian livestock farmer David Taylor with some of his beef cattle. Source: Lorna Dawson

Seeds of Knowledge: Local Expertise and Collaboration

Beyond research, Orkney’s strength lies in its people. Whilst visiting Kirkwall, I met John Muir, a 91-year-old Orcadian who has spent two decades volunteering at the Italian Chapel, helping preserve its artistry and history. Encounters like this remind me how deeply community, heritage, and care for the land intertwine.

I also spoke with Richard Shearer, the fourth generation running William Shearer, Orkney’s iconic seed merchant established in 1857. His shop truly does sell “anything from a needle to an anchor!”

Mr Richard Shearer in the gun room of his family business, William Shearer established in 1857. Source: Lorna Dawson

Richard explained how rising input costs and environmental schemes have boosted demand for clover and legumes, plants that naturally fix nitrogen, enrich soils, and support sustainable farming. His expertise exemplifies how local knowledge underpins environmental stewardship.

Looking Ahead – Research Rooted in Community

A SEFARI Gateway fellowship led by Lee Innes, Moredun, has scoped a route to a locally driven approach to agricultural research in Orkney. Agriculture is very important to Orkney’s economy, culture, and heritage. New research and technology can help improve farming and also protect the environment. Farmers need to produce food more efficiently while taking care of nature. Orkney’s people are known for being creative and making the most of their land and communities. Better communication between scientists and local people can help share useful ideas and increase the use of new technologies. A workshop was held with local people to talk about future research, missing knowledge, and how to get more involved. A Research Hub could help organise research, share results, and support teamwork and funding. Local people working with scientists can help design research that fits Orkney’s needs. New farming methods and tools could be tested using UHI facilities to make sure they work well before using them more widely. The project found new ways to teach and train people in the agriculture sector. This can help more people choose farming careers and create new jobs on the Orkney islands.

Reflections

My visit to Orkney was an inspiring reminder that this small island community is a powerhouse of innovation, collaboration, and resilience. From Neolithic builders to modern geneticists, Orkney has always been a place where people work with the land they have been given rather than against it.

Through SEFARI’s collaborative research, we continue that tradition, combining heritage with modern science and technology to ensure that Orkney’s farming, soils, and culture thrive for many generations to come.

Professor Lorna Dawson, Knowledge Exchange Broker for Environment and Soil, SEFARI Gateway